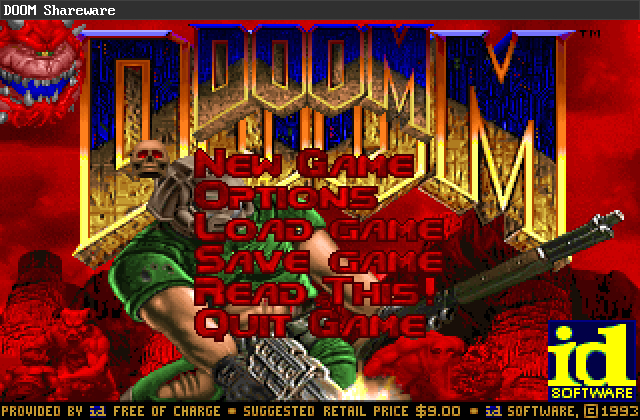

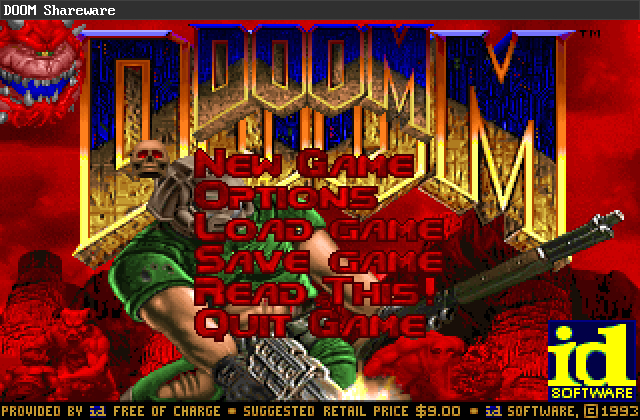

Porting Doom

Some things in life are inevitable. The passing of seasons, the fall of empires, and the porting of Doom to random platforms. In this post, we’ll investigate this last phenomenon, and how it came to happen in SnowflakeOS.

Some things in life are inevitable. The passing of seasons, the fall of empires, and the porting of Doom to random platforms. In this post, we’ll investigate this last phenomenon, and how it came to happen in SnowflakeOS.

Locally grown blog posts

Some things in life are inevitable. The passing of seasons, the fall of empires, and the porting of Doom to random platforms. In this post, we’ll investigate this last phenomenon, and how it came to happen in SnowflakeOS.

Some things in life are inevitable. The passing of seasons, the fall of empires, and the porting of Doom to random platforms. In this post, we’ll investigate this last phenomenon, and how it came to happen in SnowflakeOS.

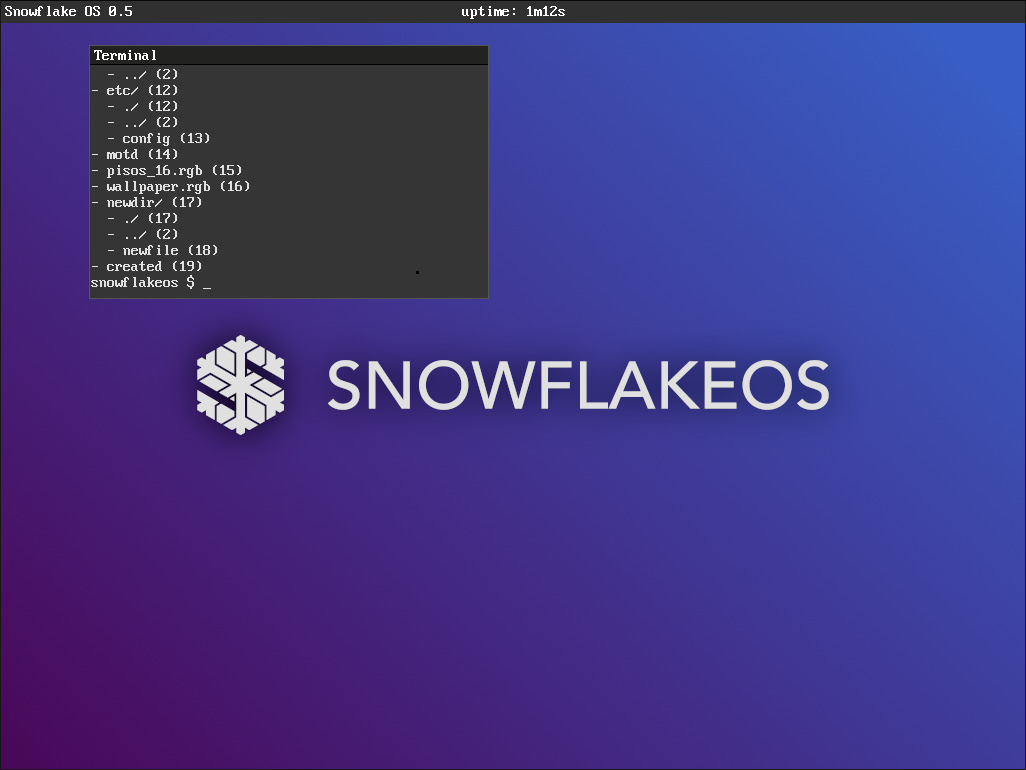

Welcome to a new post from this very irregular blog! After busy summer holidays spent hiking in the Pyrenees, college has begun again and with it, the peace required for osdev work to resume. Last time I worked on SnowflakeOS, I’d gone all in on UI work, left unfinished and unpolished. Having entirely forgotten about that work, I booted up the project and thought: “why no files? let there be files”, and now, files sort of are. Let’s see how they work, and how they don’t.

Welcome to a new post from this very irregular blog! After busy summer holidays spent hiking in the Pyrenees, college has begun again and with it, the peace required for osdev work to resume. Last time I worked on SnowflakeOS, I’d gone all in on UI work, left unfinished and unpolished. Having entirely forgotten about that work, I booted up the project and thought: “why no files? let there be files”, and now, files sort of are. Let’s see how they work, and how they don’t.

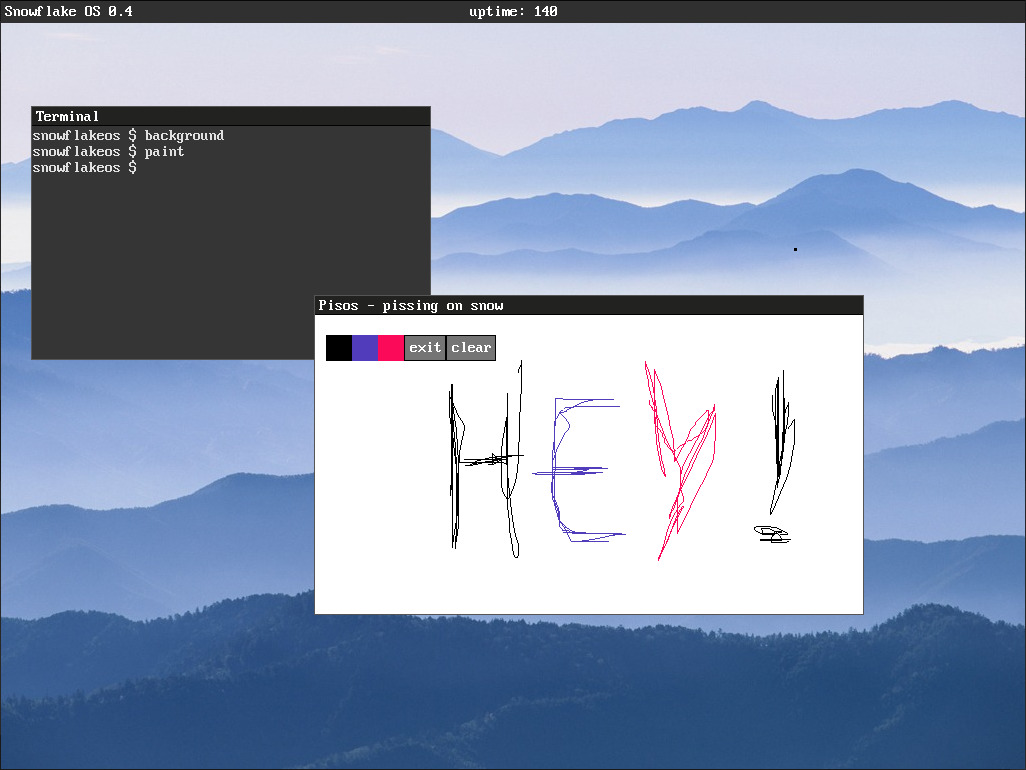

Let’s face it, it’s hard to get excited about a kernel from just barebone demos of barely functional systems. In this article, I propose a radical solution: actually implementing useful userspace programs, namely a terminal, and ye old copycat of paint.

Let’s face it, it’s hard to get excited about a kernel from just barebone demos of barely functional systems. In this article, I propose a radical solution: actually implementing useful userspace programs, namely a terminal, and ye old copycat of paint.

At the end of the last post we had a pretty solid memory allocator. Where does that take us though? Well in some cases, making hundreds of small allocations can lead to thousandfold improvements. Today, we reach for performance!

At the end of the last post we had a pretty solid memory allocator. Where does that take us though? Well in some cases, making hundreds of small allocations can lead to thousandfold improvements. Today, we reach for performance!

Today I’ll be writing about memory allocation, a fairly fundamental topic, perhaps one that most encounter faily early in their OS development journey. Yet I’ve only now started to really get into it, now that I feel like it’s needed. And it turned out to be fun after all!

Today I’ll be writing about memory allocation, a fairly fundamental topic, perhaps one that most encounter faily early in their OS development journey. Yet I’ve only now started to really get into it, now that I feel like it’s needed. And it turned out to be fun after all!

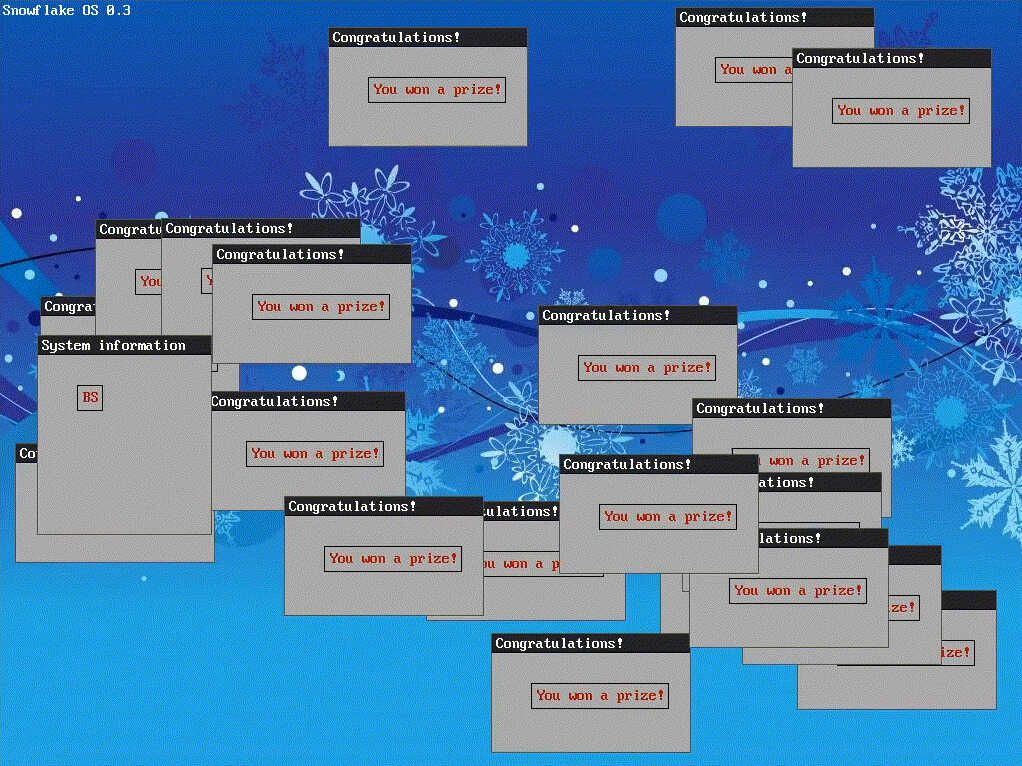

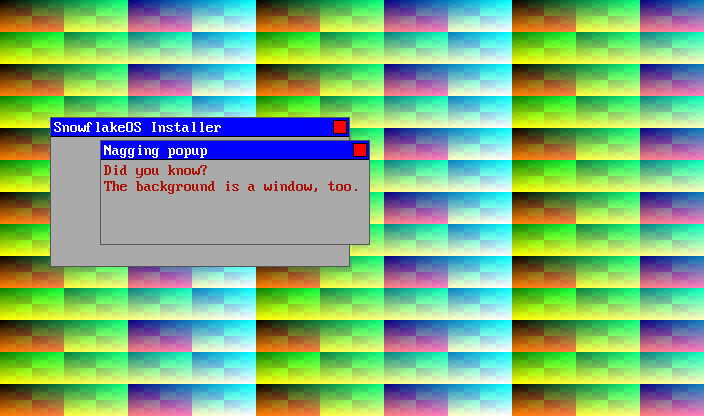

In the last post, I presented the first working version of SnowflakeOS’s window manager. While it worked, it had[1] a few important shortcomings.

In the last post, I presented the first working version of SnowflakeOS’s window manager. While it worked, it had[1] a few important shortcomings.

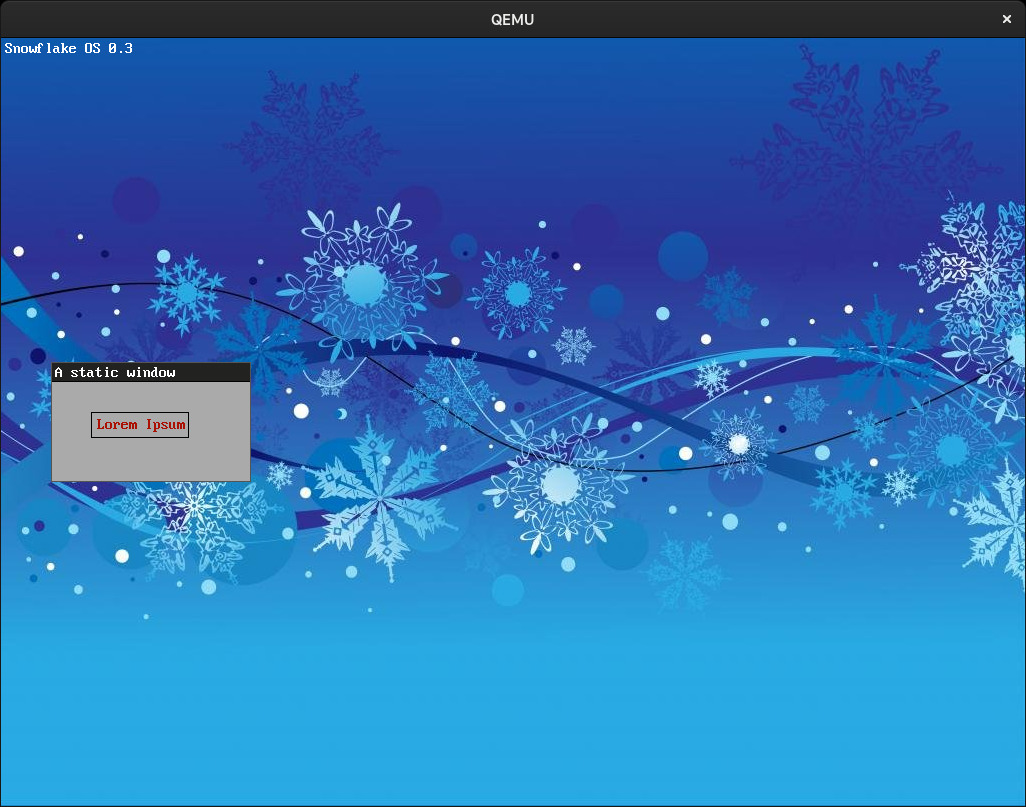

With SnowflakeOS starting to have more of the pieces a proper hobby OS should have, it was time to make this state of affair visible from the outside. Graphics!

Ironically, by switching away from text mode, we lose the immediate ability to print text, but as you’ll see we’re going to get it all back. At some point anyway; what’s presented here is the beginning of this process.

With SnowflakeOS starting to have more of the pieces a proper hobby OS should have, it was time to make this state of affair visible from the outside. Graphics!

Ironically, by switching away from text mode, we lose the immediate ability to print text, but as you’ll see we’re going to get it all back. At some point anyway; what’s presented here is the beginning of this process.

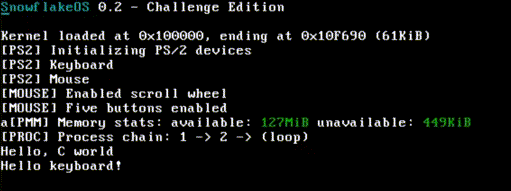

At the beginning of last week, I was looking over my keyboard code, still wondering what kind of interface could be exposed to userspace and be useful, and also wondering why my scan codes seemed to have no physical relation to any known keyboard layouts.

At the beginning of last week, I was looking over my keyboard code, still wondering what kind of interface could be exposed to userspace and be useful, and also wondering why my scan codes seemed to have no physical relation to any known keyboard layouts.

So I went over to OSDev’s article about PS/2 keyboards, which sent me to the article about the PS/2 controller, and I knew I wanted to do things properly, and at the same time, gain mouse support.

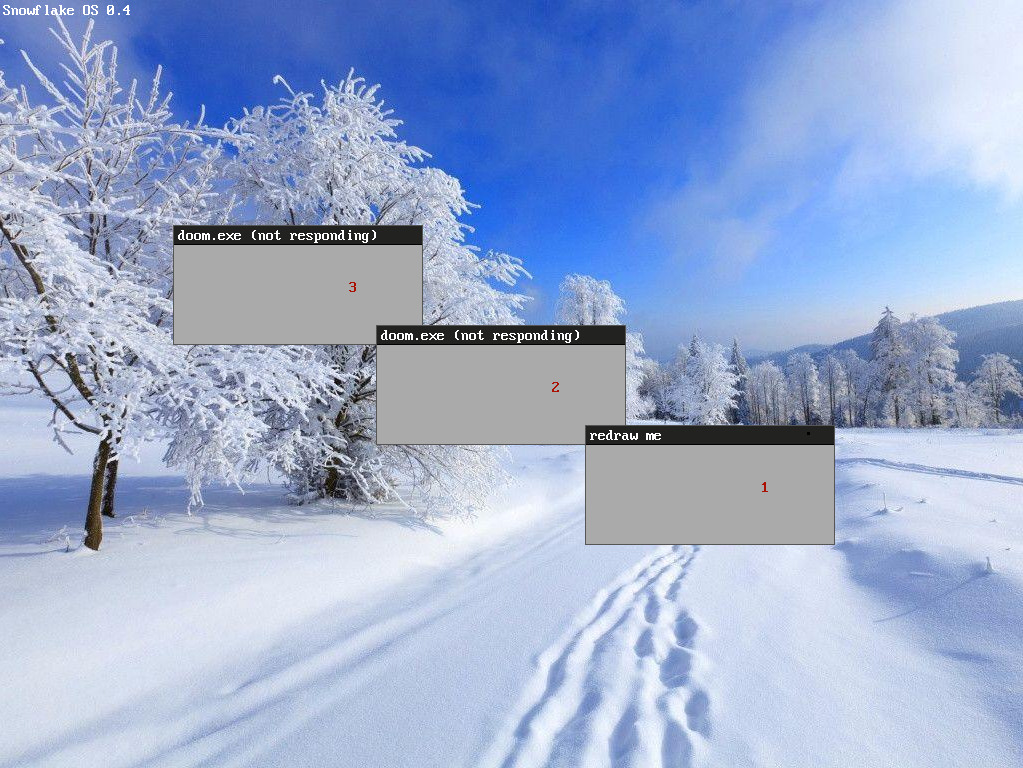

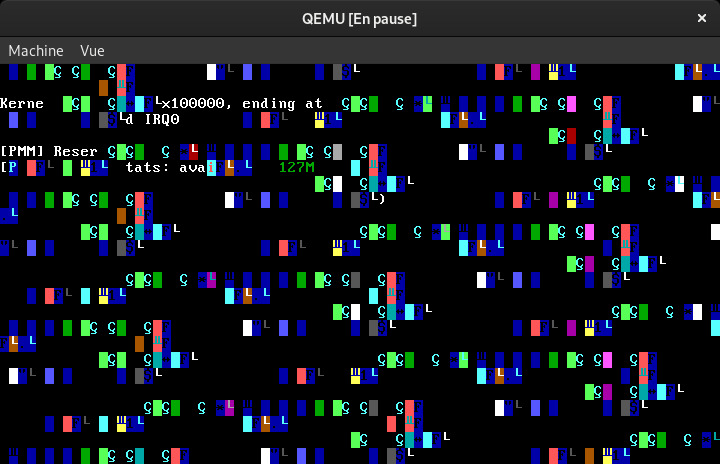

In the last post, I discussed how I implemented collaborative execution in SnowflakeOS through the

In the last post, I discussed how I implemented collaborative execution in SnowflakeOS through the iret instruction. Well, at that time the implementation wasn’t finished, even though I thought it was: I wasn’t restoring general purpose registers. This led to some pretty nice bugs, as pictured above.

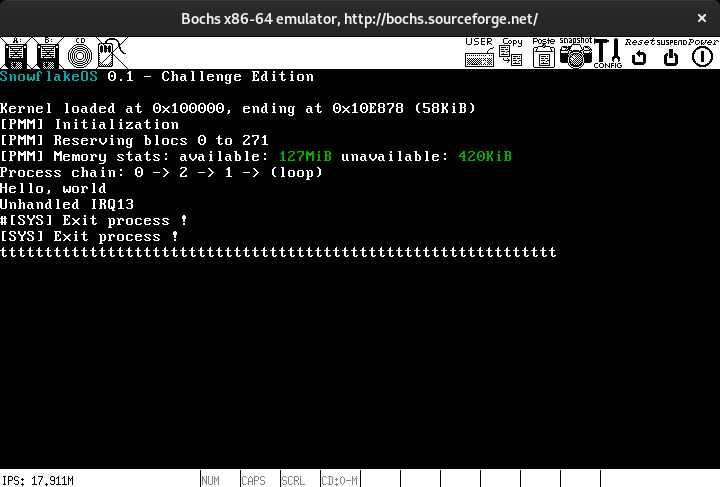

Before now, SnowflakeOS ran entirely in kernel mode, or

Before now, SnowflakeOS ran entirely in kernel mode, or ring 0. Now, the time has come for it to move on to better places, those of userland, also called ring 3.

The transition to having processes roam free in ring 3 was mostly made in the series of commits from here to there, and I encourage readers[1] to check them out.

The very first step to working on SnowflakeOS again was to setup the environment: download the sources and the tools to build them. Here’s a quick rundown.

In my first run in summer 2015, I programmed the components listed in the following categories, pretty much in that order. I’ve barely touched them since, so explaining each of them here should help me get some knowledge back.